18th February 2009 — 4th May 2009

Despite the vast length of the India-Pakistan border, there is apparently only a single road crossing between the two countries, located at the village of Wagah, where each and every afternoon, large crowds gather to watch a flag-lowering ceremony that marks the closure of the border until the following day. This precisely choreographed spectacle involves serious-looking border guards from both sides of the divide striding, stamping and goose-stepping around in an amusingly Pythonesque manner as they indulge in several minutes of high-camp faux-machismo, before finally both flags are simultaneously lowered, a very brief handshake is exchanged, and the metal gates at the border post are dramatically clanged shut. Underneath the formality and braggadocio, it's clearly a good-natured piece of crowd-pleasing theatre, and beyond that a perhaps important display of the fragile and necessary mutual respect that holds between these fractious, nuclear-armed neighbours, played out day after day over this singular threshold.

Amateur video footage of this remarkable ceremony, taken from YouTube, comprises one of the more unlikely exhibits in the Hayward's current group show, curated by Mark Wallinger and based around the theme of frontiers, borders and thresholds. The video is as good a starting point as any into Wallinger's eclectic selection of work, and rather like the exhibition as a whole, it's fascinating if also a little frustrating. The scrappy and un-contextualised video footage is devoid of any direct reference to the many deeper issues concerning this controversial borderline (created when the British government's man hastily carved the partition in 1947), and whilst there is no explicit attempt here to expound on the topic any further, this proves to be typical of Wallinger's approach, which consists of presenting us with an incredibly wide and diverse range of subjects, forms and ideas, within both the gallery and the accompanying publication, and mostly leaving it to us to ponder what it might all add up to.

This is perhaps all well and good: allowing the viewer free rein to forge their own dialogues and connections between things is par for the course, typical of current approaches to these kind of shows, and not entirely unwelcome. However, Wallinger seems determined to shoehorn such a breadth of ideas into the project - he certainly isn't one to subscribe to the ethos of 'less is more' - that his putative theme sometimes becomes somewhat diluted under the sheer variety of different material. On display a few feet away from the YouTube footage is an early Roman marble sculpture - a double-headed herm depicting the heads of Dionysos and Silenus – which is perhaps as far away from the pop-cultural tone of YouTube as it's possible to get, and gives an idea of the broad spectrum of work that's included. Along the way we're invited to contemplate everything from Edweard Muybridge's famous photographic studies of motion, to Fred Sandbank's spare and elegant lines of yarn hanging from the ceiling and across the floor, to Tacita Dean's entertaining video of foley artists at work, via some wonderful Durer woodcuts, a dreary painting of Jerusalem by Richard Carline, Wallinger's own horrible pair of vases containing gaudy plastic flowers, and much else besides. Sometimes this feels like eclecticism employed for its own sake, as though Wallinger is keen to impress upon us the broad-mindedness of his taste. More often than not though, he succeeds in generating some fruitful and stimulating juxtapositions.

The exhibition catalogue is also an integral part of the project, and further muddies the waters or adds to their glorious depths depending on your point of view, with copious and sometimes opaque reference to James Joyce (Wallinger wrote his MA thesis on Ulysses), verse by the likes of Goethe and Keats, amusing and insightful accounts of events from Wallinger's own life, and snatches of prose dealing with subjects ranging from sleep deprivation to playing tag in the school playground. This latter passage threw up an intriguing idea. Apparently, the rules of tag permit you to cross your fingers and declare 'fay knights', which renders you briefly exempt from the normal rules of the game. Wallinger makes the suggestion that 'perhaps art exists in such an interregnum', which is an inspired analogy, and helps to throw some light on the thinking behind some of his selections.

Indeed, the show is most successful when it places us in these kind of uncertain, liminal zones. This is brilliantly achieved in a version of a Marcel Duchamp piece that consists of a single door hung so that it opens on two doorframes set at right angles. Something of a double-take ensues before we realise the door's playful dual function and its status as a work of art; what's more, it's installed in the Hayward so that it isn't immediately clear whether the areas beyond these doorways form part of the exhibition space, and whether we're supposed, or permitted, to traverse either of these thresholds, resulting in a moment of hesitation. In something of a curatorial masterstroke, placed immediately next to this work is a William Blake etching called Death's Door, illustrating lines from Robert Blair's poem The Grave, and depicting an old man stepping through the doorway of his own tomb. After being mildly confounded by the question of crossing Duchamp's doorways, Blake's meditation on passing over life's ultimate threshold now delivers a real existential jolt. Perhaps death will present us with a choice of doors.

Another piece that invites our physical participation in order to skew our awareness of space is Monika Sosnowska's Corridor installation. We step into a passageway and turn a corner, at which point there's a delicious sense of surrendering oneself to the environment the artist has created, before it becomes clear that to do so, and to continue to progress through the corridor would involve defying the laws of gravity, as the carpet takes a turn for the vertical. In submitting to Sosnowska's subversion of spatial logic, we're literally sent round the bend and driven up the wall. In this way, arriving at the end of the corridor feels a bit like arriving at the borderline between sanity and madness; and so at the same time, this is a work about the power of imagination: about the prospect, and the price, of transcending the boundary of the possible.

Watching Bruce Nauman in his early video piece, Revolving Upside Down, feels like observing a man who has long since crossed that particular border. It's one of a series of videos Nauman made in the late 60s, and finds the artist seemingly hanging, bat-like, from the ceiling of his studio, slowly and interminably rotating on one leg. Of course, Nauman has achieved this effect by simply turning the camera upside down, and yet it's surprisingly easy to imagine that having climbed the walls in a crazed search for what to create, he's found himself, and found his answer, in this precariously inverted state. Suspending disbelief in order to, well, suspend.

All manner of inversions, mirrorings and doublings abound in this show, to the point where this is what almost feels like the exhibition's overriding theme. Possibly the most satisfying exploration of this is Amie Siegel's twin screen video installation, Berlin Remake, in which scenes from old East German films are shown alongside Siegel's witty shot-for-shot recreations. It's a simple and brilliantly realised conceit, and results in a work that invites reflection not only on the influence of the Berlin Wall, and the reverberations that the old border continues to exert today, but on our changing relationship to public space and the history it embodies, on the spectral nature of moving images, on both timelessness and the passing of time.

It's nearly twenty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, and nearly eight since another epochal fall – that of the twin towers of World Trade Centre: a manifestation of doubling at its most monumental, and ultimately of course, at its most devastating. They clearly continue to haunt Wallinger, and loom large over this exhibition. Included here is a video of NBC news footage, shot from a helicopter, of the tightrope suspended between the towers in 1974 by Philippe Petit for his now infamous high wire walk. The exhibition guide notes that this was the only point in their existence that the towers were joined. One could perhaps point out that they were to be united again in their destruction. Displayed next to this footage is a ghostly and weirdly prescient Joseph Beuys lithograph from 1975 showing four images of the towers, coloured with an almost blood-orange tint, and labelled with the names of the Christian martyrs Cosmos and Damien. Similarly prophetic is the reference in the catalogue to Jean Baudrillard's assertion in 1983 that the 'tactical doubling of forms, of monopoly in duopoly' that he identified in the World Trade Centre, would be brought down by Islam.

The show contains a number of other similarly eye-opening revelations, and even if it sometimes seems as though Wallinger has thrown so many of his passions, interests and anecdotes into the project that any unifying thread is at risk of being drowned under the abundance of stuff, it's undeniably a rich collection of material that rewards you the more you engage with it, and the longer you tarry in its interregnums.

David Foster

Anon

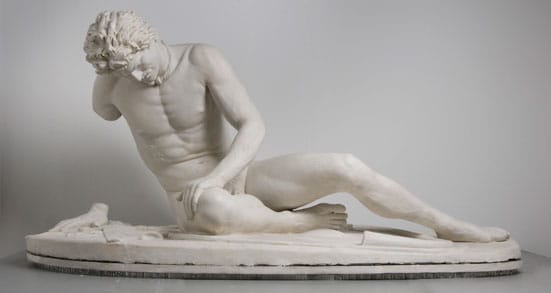

The Dying Gaul (1822)

Photo credit: John McGregor, eca Photographer

RENATO GIUSEPPE BERTELLI

Continuous Profile (Head of Mussolini) (1933)

© Renato Bertelli 2009

Mark Wallinger

Time and Relative Dimensions in Space, 2001

Stainless steel, MDF, electric light

281.5 x 135 x 135 cm

Courtesy Anthony Reynolds Gallery

© the artist 2009