25th June 2011 — 25th September 2011

I suspect that like many people, I first encountered the Latin phrase ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ at the beginning of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, and just as these words serve as the starting point, as well as casting their shadow over the whole, of Waugh’s great novel of life, love, belief and death, so the motto might be seen to function in a similar manner in this exhibition, which pairs the work of 17th-century French master Nicolas Poussin with that of the American artist Cy Twombly, who died just a few days after the show opened. The two artists’ wildly different meditations on this immortal (or rather, perhaps, mortal) phrase combine to form an inspired jumping-off point in the show’s opening section; the themes, contrasts and ambiguities that it introduces then permeating through the whole of what is mostly a terrifically stimulating exhibition.

Of course, the phrase ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ (usually translated as ‘I am even in Arcadia’ or ‘I am also in Arcadia’) is well-known chiefly because of its use by Poussin in his two versions of The Arcadian Shepherds, where it appears as an inscription on a tomb being deciphered (or not) by wandering shepherds. The earlier and to my mind far superior of the two versions is shown here, Poussin treating the scene with great tenderness and pathos, quietly expressing the dual beauty and tragedy of death’s inevitability and life’s transience – the latter reflected by the flow of water poured by the downcast figure of the river god Alpheus at the foot of the tomb. This painting is juxtaposed with Twombly’s Arcadia, a large grey expanse covered in a confusion of his customary scribbles and scrawls, amongst which we can certainly discern the titular word, and unless I imagined it (which is possible), can just about make out the other words of the aforementioned memento mori. There is certainly a sense of Twombly furiously working through his feelings about the phrase, or about the very notion of Arcadia: a sense of repeated and repeatedly abortive attempts to enunciate his thoughts, both conscious and unconscious, as he fails to grasp, or accept, its ambiguous and ultimately unknowable meaning.

After all, it is surely the polysemy of ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ that largely accounts for its enduring resonance over the centuries: Arcadia could arguably refer to both an earthly idyll or a post-mortem paradise, and the ‘I’ is sometimes taken to refer to the occupant of the tomb, or sometimes to death itself. However we choose to interpret the phrase, it’s clear that whilst the theme of death suffuses both of these works, it does so in a manner that, as with perhaps any profound exploration of mortality, recognises that a meditation on dying must also be a meditation on living. The same can be said of Twombly’s sepulchral sculpture Pasargade, which, although small, dominates the centre of the first room. Indeed, this is the first thing you encounter as you step into the exhibition, and it’s impossible not to reflect on Twombly’s own life and its end as you behold this haunting, tomb-like object. Whilst its form rhymes with Poussin’s Arcadian tomb, its cream and white surface and pencilled verse fragment on the theme of light are rhymed with the washes of cloudy sky in an untitled pair of Twombly’s paintings displayed a few feet away. Inspired by the Italian countryside around Bassano in Teverina, these two similar works on cruciform-like panels are prime examples of the artist’s embrace in the second half of his career of a painterly expressionism, and are simple yet captivating evocations of the natural world: paintings that carry out the paradoxical work of capturing things in flux – the passage of clouds and of light, the flowing of water. The latter sends us back once more to Poussin’s Alpheus, and we realise, not for the last time, that Twombly too is invoking the old gods: that the religious overtones of the panels’ shape suggest the worship of nature itself.

Or in other words, something like Pan, the subject and title of another piece by Twombly a little further on in the show, which is displayed alongside his work Bacchanalia: Fall (5 days in November), and an untitled resin sculpture of a pan pipe. Naturally, these are all paired with one of Poussin’s three Bacchanals, namely The Triumph of Pan, an exuberant tableau of drunken revellers cavorting around a herm of Pan (or possibly the closely related divinity Priapus) in the centre of the picture. It’s a vibrant, dynamic scene by Poussin’s often overly mannered standards, and there’s something slightly unsettling and uncanny about the red-faced idol silently grinning at his indulgent worshippers. The dialogue created between this and Twombly’s Bacchanalia is a richly rewarding one, and perhaps the highlight of the show. Twombly’s piece presents us with a great violent smear of reds, browns, and off-whites, in oils, pencil, chalk and gouache, running from the left to the right of the paper, brilliantly condensing the heady, visceral, swaying energy of the Poussin into something of its underlying rhythm and tonality. The work evinces the darker, uglier side of a bacchanal, eliciting the intimation of foreboding we see in the mad face of Poussin’s herm. Twombly’s evocative subtitle — Fall: 5 days in November — adds something too, which along with the main title is scrawled across the paper in a suitably deranged fashion. The piece also includes a reproduction of one of Poussin’s similar Bacchanal drawings collaged onto the work (the original of which is also displayed here), which seems like a redundant and ungainly appendage in this context, but would perhaps make sense were one seeing the piece displayed without the real thing alongside.

The preceding room deals with the two artists’ approaches to love and eroticism, and unsurprisingly both are bound up again with the theme of death. A number of Poussin’s works explore the closeness of this relationship, and the one displayed here is Dulwich’s own Rinaldo and Armida, a painting depicting the moment when the sorceress Armida, on the cusp of murdering the sleeping crusader Rinaldo, instead falls in love with him. Whilst this memorable image captures a moment of intimacy between love and death, Twombly captures their out-and-out intermingling in his exhilarating canvas Hero and Leandro (To Christopher Marlowe). This large, sensual painting – one of several of the artist’s works based on the story of the doomed, drowned lovers – finds Twombly in unabashedly romantic mood, as a torrent of whites and pinks rush across the canvas in a great wave of consummation and subsumation.

The show is not without its faults, and next to this work is Twombly’s much cruder Venus + Adonis, a piece from the same period as the Bacchanalia series, but infinitely less successful, partly because, without any of Poussin’s renderings of the myth on display here, it appears to bear no relation to classical imagery, and just seems like an awkward daub. Viewing it alongside Poussin’s Venus and Adonis, as we can in the exhibition catalogue, Twombly’s version begins to appeal slightly more. Perhaps the owners refused to lend the work, so instead we get Poussin’s Venus and Mercury, which only serves to make the Twombly look even more gauche by comparison, so weightlessly is Venus rendered, so expertly does Poussin express the tussle between erotic and spiritual love, and the pull and excitation of both.

There are a couple of slightly odd rooms in this exhibition, where the connections between the two artists are rather strained. Pairing Poussin’s The Triumph of David with Twombly’s Herodiade, seemingly because both deal with stories involving beheadings, makes us see neither work in a different light, and the curator’s efforts to draw compositional affinities between them are a little forced to say the least. The room devoted to Apollo, Parnassus and poetry is similarly disappointing, partly because the works on display show neither artist at their finest.

However, there are some unlikely and provocative juxtapositions that, on reflection, are remarkably effective. The pairing of Poussin’s preparatory study for Joshua’s Victory over the Amonites - a dense and chaotic tangle of surging bodies - with two of Twombly’s untitled pieces of frenzied, illegible scrawl, works to bring out the frantic energy of the former, and emphasises the senselessness and violence in the latter. The exhibition commentaries repeatedly insist on the ‘calligraphic’ nature of the scriptural aspects of Twombly’s work, but this is misleading and imbues his childlike mark-making with an erroneous and unnecessary sheen of politesse. I’m pleased to say that there’s nothing in Twombly’s art akin to the prim elegance of calligraphy – a word that derives from the Greek for ‘beautiful writing’ - but only its opposite: his scrawls are far better described as a form of cacography, and at their most compelling, as in these two pieces from the mid-50s, they seem to work themselves up into a frantic, almost primordial anguish through their frustrated efforts to form a coherent expression.

The final room of the show contains only Twombly’s magisterial Quattro Stagioni (A Painting in Four Parts), perhaps his best-known series of works (there are two sets: the other is at MOMA), and probably the high watermark of his career. Poussin’s The Four Seasons are in The Louvre, and presumably wouldn’t be lent, but whilst it’s a pity not to see them all side by side, any chance to gaze once again at Twombly’s interpretations of this perennial theme is more than adequate compensation, as reproductions don’t even begin to do justice to these works. I particularly like Estate (summer): a shimmering, dripping melt of yellows, creams and whites, interspersed with some wonderfully enigmatic verse fragments, some of which are of Twombly’s own creation (‘Ah, it goes, is lost in white horizons’).

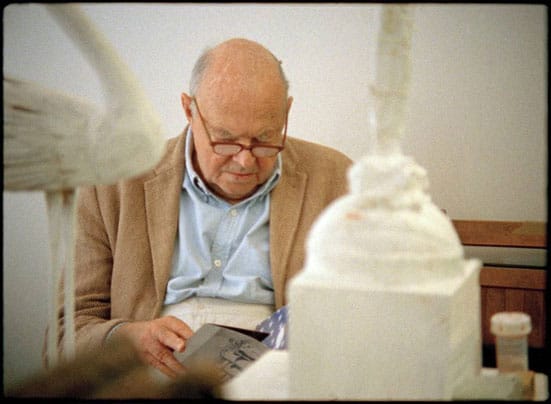

The theme of the seasonal cycle – and indeed the circadian cycle - continues in an adjunct to the exhibition: the first showing of Tacita Dean’s half-hour film of Twombly, called Edwin Parker, which was his given name. Dean filmed Twombly last autumn in his studio in Lexington, Virginia - his place of birth, and the town he used to return to from Italy once a year – and we see him over what appears to be the course of a single day: talking quietly with his assistants, taking lunch at a diner, re-reading a letter, and generally attending to his affairs. We know what to expect from Dean’s work by now: a peaceful, pensive quietude; the warm, slightly nostalgic, romantic texture of her 16mm film; and an ability to somehow absent herself and her camera from what she’s filming. Her portrait of Twombly begins by observing him from afar, so that we only glimpse him through a small gap, as though slightly timid of approaching someone who has spent much of their life avoiding the public’s gaze (Dean herself has noted that she only recently found out what he looked like, despite being a great admirer of his work). Then abruptly, his face is seen in close-up. He looks like a man irresolute, in limbo, and especially given recent events, it’s difficult not to think of this as a portrait of a man preparing to die. Dean’s imagery undoubtedly encourages this approach - the camera lingering on passing shadows, on blinds coming down, the film ending with contemplative shots of a tree clinging to its last few leaves and of his studio in the twilight – and indeed she has considerable form in making films about artists in the twilight of their days: Mario Merz, Michael Hamburger, and Merce Cunningham all died shortly after she filmed them. An echo of ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ resounds throughout Deans’s oeuvre, and appending the exhibition with her tribute to Twombly is an ideal way for it to end: by sending us back to the beginning.

David Foster

Nicolas Poussin, The Arcadian Shepherds (c.1629)

Oil on canvas, 121.6 x 96 x 6 cm, © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth.

Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

Cy Twombly, Bacchanalia-Fall (5 Days in November) Blatt 4, InvNr. UAB 457, 1977

collage, oil, chalk, gouache, on fabriano paper, graph paper, 101.2 x 150.5 cm

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Museum Brandhorst, München.

Leihgeber: Udo Brandhorst, © Cy Twombly

Tacita Dean, Edwin Parker 2011

16mm colour film, 29 minutes,

COURTESY THE ARTIST, FRITH STREET GALLERY LONDON

AND MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY NEW YORK / PARIS