11th June 2013 — 26th August 2013

Hmm, forgive me if I’m musing about something that you’ve already developed sophisticated opinions on, but it’s the vexed question of what exactly constitutes outsider art? And why is it outsider? And how does one become an insider?

A curator friend with whom I was queuing for the other crazy spaceman cometh exhibition in town, the Big Bowie Show at the V&A, observed, with a degree of asperity, that at least half the work at Venice this year is auto-didactic. I read into the undertone of irritation the frustration of an academic who prefers following the careers of artists who have put in their time parsing and being influenced by the works of past and present masters, straining to distil concepts into exquisitely rarefied formats. These auto-didacts and their effortful representations – by and large the work is referential, ie. not abstract, straining to communicate an idiosyncratic vision of the world, in often eye-watering detail – they’re just not cool.

Her son, who is not yet two, will never be an outsider in the hillbilly sense. By the time he hits primary school, he will have participated in scads of kids’ workshops in art galleries, worn many sets of headphones, overheard countless ripe judgements confidently expressed on art and artists, been asked to point at his favourite pieces in exhibitions or watched his mother and father gasp in wonderment at brave new works ... Absorbed visual values of the art world (not necessarily coherent, by any means). Fully inside, then, stylistically, culturally ...?

But actually perhaps this is all missing the point. Insider-outsiderness is not just about influences. Hingeing on accepted versions of reality and digestible plausibility, it also comes down to personality. An Alternative Guide to the Universe at the Hayward exhibits a series of often verbose, obsessive, meticulous visionaries who, to be facetious, would make challenging pub company. I am being facetious because often the pain and the isolation and the art-as-therapy that are here borne witness to provoke physical, visceral reactions. Whether they are ‘in’ or ‘out’ anywhere feels laughably irrelevant; such fussy delineations feel silly and trite. This isn’t art for money – nor about artworld acceptance. Or, at least if it is, it is the most uncynical exercise imaginable. It is all heart, all sincerity, all message. Which can be hard for a world-weary urbane sophisticate to have any patience for.

To underline this point the show is in conjunction with the Museum of Everything, ‘the British and worldwide wandering institution for the untrained, unintentional, undiscovered and unclassifiable artists of modern times’, whose message outside the exhibition reads: ‘And if you don’t believe that we were all born to make, that the title of artist is a human right and that creativity is what being alive is all about, then perhaps this isn’t the show for you.’

Ok, enough word-wasteful preamble, onto the art, which will be damned hard to describe succinctly. The show is grouped by overlapping big ideas (and they are enormous): Outer space. Alien Life-forms. UFOs. Ideal architecture. Future cities. Healing Cities, Blueprints for a ravaged society. Organic architecture. The power of numerology. What the world is really made of. The power of reinvention. The furtive lure of creation.

What unifies the exhibition is the incredibly disciplined and careful signage. Detailed but neutral, it respectfully eschews irony or humour or the canyoubelieveit?! tone unavoidable when the works are being discussed outside such a studiously ‘opinion-free’ zone. The show opens uncompromisingly with Paul Laffoley’s ultra-worked painting systems, like the Detrorotatory Indicator for Time Travel into the Future and The Third Arrival of Quazgaa Klaatu (a work through which one can communicate with extraterrestrials), and the Eloptic Nohmagraphon Containing the Modalities of the Tulpodial Urtraum, which for the unconverted are clearly vulnerable to mockery. For me, I have to confess the chief delight was a guilty, slightly antsy wonderment that the incantatory fervour evidenced by the slick, finessed realisation of the works was genuine and that this straight-out-of-Pratchett language was sincere neologism of the zyrgiest order. It attests to a commitment to a worldview that utterly defies detraction.

There is much special naming in evidence. During the 1930s A. G. Rizzoli drew symbolic portraits of family members or friends as buildings, or ‘heavenly inheritances architecturally expressed’. The perfect realm that they might inhabit was Y.T.T.E. (Yield to Total Elation). And his work is rapturous. In 1935 he held a one-day exhibition A.T.E. (Achilles Tectonic Exhibit) in his house, which was commemorated annually for the next five years and in which visitors to the exhibition were celebrated in large, magnificent ink and pencil drawings. Apart from some immediate family members, the few visitors who came were mainly local children. Grace M. Popich is depicted as a grand circular tower-fort, with beaming torchlight; the following year, when Rizzoli’s younger sister Palmira and her husband visted from Monterey, they were sparklingly represented as a domed Palais Pillon; and his commemorative portrait, a year after her death, of his mother, known as The Kathedral, is a grandiloquent High Gothic extravaganza. Rizzoli was a life-long virgin and perhaps the most extraordinary work on show is that depicting the stages of his ‘highly fascinating puzzled wonderment’ in reaction to the only human being he’d ever seen naked, the three-year-old child of a neighbour. The Primal Glimse at 40, subtitled ‘THAT YOU TOO MAY SEE SOMETHING YOU’VE NEVER SEEN BEFORE’, is, to all intents and purposes. a very pointy skyscraper... Calling himself ‘The Delineator’ he explains himself to be ‘in appreciation’ that he had ‘delineated architecture unique to extremes hardly possible unless one has actually experienced the actually intrinsic throbbing ordeal’... Oo-er.

The next room is an Ooher of a different order: in hushed lighting, vividly rendered in pencil, then translucent inks and varnish, fabulously intricate drawings by Marcel Storr made in the 1980s are beautifully backlit in lightbox frames creating their own richly jewelled mini-cathedral of blueprints for rebuilding Paris in the event of nuclear attack. High Gothic sits beside Angkor Wat, pagodas, la Sagrada Familia and Vegas, in oranges, yellows, cyans, reds, purples, dark greens, often against soft pink skies...

Calling himself a time traveller, George Widener is also described as a Calendar Savant: he incantates using magic squares of numbers and honours auspicious dates in formally beautiful grids. ‘Numbers are my friends. I build a land for them to live in.’ He really gets going for me when rendering his future megalopolese, inc. Megalopolis 2053, where order, function, balance, manners and singularity are the laws for the future. Round checkerboard cartoon buildings and spaces fizz and hum, not so much providing an architectural blueprint as a manifesto for courteous two-tone humungousness.

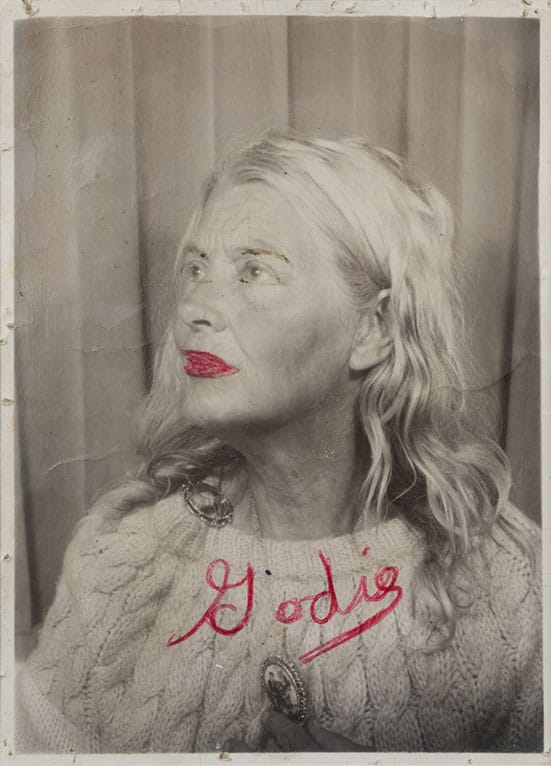

Upstairs Lee Godie, a homeless artist in her sixties, who was born and died in Chicago, is seen photographing herself in booths, often browned up with instant iced-tea mix, sometimes posing as a vamp, pouting, hair piled on her head, in an off-the-shoulder number, or holding various props: roses, magazine covers, money earned from sales of her paintings fanned out. Eyebrows are often drawn darker afterwards, in a way that emphasises the full-frontality of her bulbously staring engagement. Next door are the creepy half-size anatomically correct girl and boy dolls carved by Morton Bartlett and carefully photographed to emphasise their life-likeness in clothes knitted and sewn by himself. The strange neutrality of the images almost seems to echo the innocent confusion of Rizzoli downstairs, except that then it doesn’t, at which point I had to walk away. Except that I couldn’t, as Wu Yulu’s (China’s Brightest Farmer-Inventor 2004) uncanny valley robot doll-child - designed to chase people - came buzzing down the corridor into a group of American students. All the women freaked, as did I, when borne down upon by this inexorable Bambi-eyed as it seemed to sniff out reluctance and home in on it.

Then, mercifully, to Jean Perdrizet, inventor of robot cosmonauts to be humanity’s ambassadors to the cosmos, and creator of Sidereal Esperanto, the celestial language for robots on the moon, using ‘92 signs of a typographical typewriter, the keyboard of thought’. Large, chaotically scribbled sheets and diagrams in coloured pencils and pen, including one large drawing of a robot worker were among the documents that he sent to NASA and the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, in his campaign for a Nobel Prize.

Emery Blagdon’s wonderful Cornelia-Parker-esque hanging sculpture was created in the belief that our planet’s electromagnetic forces contain curative powers. His Healing Machine in wire, copper, aluminium foil, Christmas-tree lights, ribbons, beads, leaves, butterfly wings, magnets, cogs, snuffboxes, is delicately wrought, in series and hung in a circle, alongside coloured paintings intended to be placed face down on the earth to contribute to the overall energy flow.

Sharing the room is Melvin Edward Nelson, who lived on a farm in Oregon in the sixties in an area known for its UFO sightings. His Original Astro-Planetary Art records our planet and other worlds as he saw them during astral projections – he made his pictures using stardust and sacred pigments collected from UFO landing sites on his farm. The works on paper, mostly circular or elliptical have a curious grace and precision; the drying earthy pigments tug inward on the paper, suggesting some sort of centrifugal force.

Karl Hans Jenke insisted that his doctors patent his inventions which he continuously produced during a life of seclusion in a rural mental asylum in Eastern Germany. Staying abreast of developments in engineering, rocket science and renewable technology, he discovered the ‘radiation-free German Atom’. His paintings are beautiful Boy’s Own treatises: the rockets’ inner combustion chambers, all Flash Gordon reds and yellows, are housed inside silvered engines, like the awesome Deutsches Atom-Triebwerk of 1957. These sit alongside beautiful all-known universe paintings, titled Origin of Life, Return from Venus, Suns and Planets and the Highway Route of Our Space Projects. The Donne line ‘One little room an everywhere’, comes to mind.

My favourite piece of the show, Colour Letter Racer Set, by the hiphop pioneer, MC and sculptor Rammellzee (1960-2010, Queen’s, NY), comes careering out of the sky, a mutant army of some fifty customised skateboards hung from the ceiling, built up with fluo-painted styrofoam, cardboard, rockets, speakers, white goods scrap, 2-d red& yellow faces, claws, increasing in size towards the back and curving down towards the spectator, ‘poised for linguistic and galactic warfare’. Rammellzee imagined a world in which letters of the alphabet would arm and liberate themselves from the slavery and corruption of language. The inherent energy of the work is itself exciting, but there is also a welcome respite from labyrinthine works-as-manifestos that demand feverish involvement.

The show is pleasingly curated to sandwich the downright disturbing and difficult between the intriguing and the gleeful. In the difficult category, because I’m crap at traditional maths/physics, so the clevernesses of the alternate calculations are lost on me, I have avoided trying to describe the work of James ‘No Such Thing as Gravity’ Carter, who believes that clouds are caused by the tears in the atmospheric layer that occur as a result of the earth doubling in size every nineteen minutes, or the knobbly mathematics-made-sculpture of Philip Blackmarr’s quantum geometry...

So finally, back to the beautiful and utopian: Bodys Isek Kingelez, born in 1948 in Congo, previously shown in the Hayward’s Africa Remix, in 2005, started making his urban utopias for the 3rd Millennium in the 1980s despite never having left Kinshasa nor having ever seen even any photographs of any other city. These colourful cardboard, foil and plastic fantasias are designed as parts of whole cities: his Kinshasa for the third millennium is ‘a free peaceful city, where delinquents, police and prisons don’t exist’.

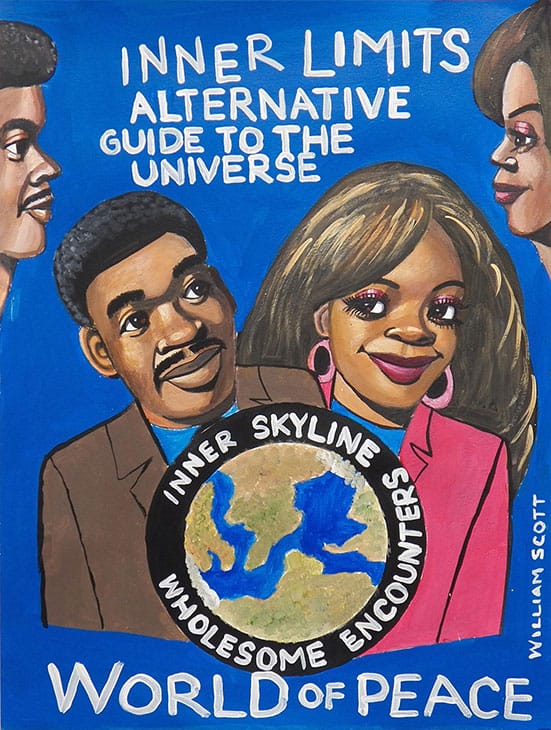

Which brings me, gleefully, to the wonderful William Scott: born in San Francisco in 1964, he envisions a reinvention of that city into Praise Frisco, a gleaming, safe, peaceful city, infused with Gospel Festivals, spiritually and psychically transformed, with emphasis on dancing and happiness (and it would appear smiling, doe-eyed, long-lashed booty blessed Jackie Brown lookalikes). Such a metamorphosis would be the result of wholesome encounters between Skyline Friendly Organisations (UFO)s and the local Baptist Church, which would enable people to reinvent their lives. The whole is solidly painted in 1970s TV cartoon-like blues and pinks, with warmth and delight.

And the gentle wonky buildings, created by Richard Greaves in the wilds of Canada, to move with the wind, held together with string, because it doesn‘t hurt the wood, seem to remind us to protect our dreamers, our lonely prophets and to mind our own wishfulness.

Because aren’t all artists difficult bedfellows sometimes? It is what Martha Graham termed that ‘queer divine dissatisfaction’, that ‘blessed unrest’, that keeps those ornery, pesky creatures marching, autodidacts or otherwise. What finally charmed me was that this exhibition is also in conjunction also with the Festival of Neighbourhood, because aren’t we all in this together, cheek by jowl, each with our own weirdnesses, our own tics, our own need for forbearance, understanding and a kindly ear?

Fiona McHardy

Paul Laffoley

The World Self (1967)

Installation view ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’, Hayward Gallery 2013

© the artist

Photo: Linda Nylind

Marcel Storr

Untitled (1975)

Installation view ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’, Hayward Gallery 2013

© Liliane and Bertrand Kempf

Photo: Linda Nylind

Lee Godie

Lee and Cameo on a chair... (early to mid 1970s)

© the artist

Courtesy Richard and Ellen Sandor Family Collection

Yulu Wu

Remote Controlled Cart with Clothing (Yao Kong Chuan Yi Xiao La Che) (2013)

Installation view ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’, Hayward Gallery 2013

© the artist

Photo: Linda Nylind

Emery Blagdon

Healing Machine (c.1950-c.1980)

Installation view ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’, Hayward Gallery 2013

© Calvin Morris Gallery, New York, NY

Photo: Linda Nylind

Rammellzee

Color Letter Racer Set (c.1988) and White Letter Racer Set (c.1991)

Installation view ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’, Hayward Gallery 2013

© Estate of Carmela Zagari Rammellzee

Photo: Linda Nylind

William Scott

SFOs The Skyline People of Wholesome Encounters Of A New Science Fiction Future (2013)

© Creative Growth Art Center

Courtesy of Creative Growth Art Center