Nick Hornby: Atom vs. Super Subject

Alexia Goethe Gallery

Dover Street

21 May–9 July 2010

I met Nick Hornby in January 2008 in a café in Shoreditch. We were both attending a symposium on collecting live art and were in need of strong caffeine. He was about to receive the Clifford Chance sculpture award. Somehow there was something in what we talked about that made me want to go and see this show. Something that was beyond the drinks served on the top floor of a tower in Canary Wharf. That something was the feeling of being in the presence of an artist. Someone who can bring to us a view of the world that will change us. His presence at the Canal Museum in a group show curated by Brooke Lynn McGowan was both playful and assured. A sense of an artist engaging with subjects and form, placing himself in the tradition of modern art and resolutely departing from it. This was soon followed by a piece made with the jazz musician Soweto Kinch as part of Altermodern, the Tate Triennal show in 2009. A work made with young people which opens the way for the piece made for the Southbank Centre with six young people.

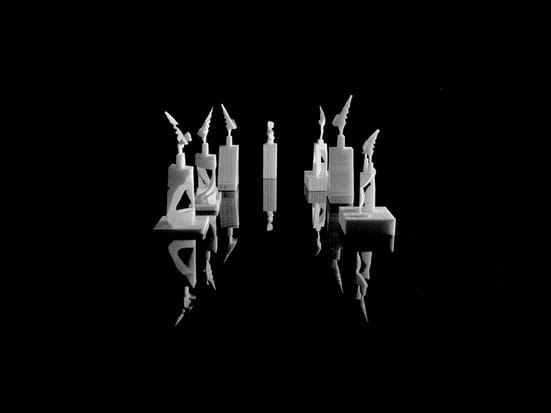

Last month Hornby opened his first solo gallery show in London with a set of new works in one medium but different scales.

FB: First show in a London gallery, how does it feel?

NH: I've done some projects in a pond, in a car-park in a canal museum, in the Tate and Southbank, with large and small budgets… and they all feel the same. In this case, Alexia's space is quite particular – it has a huge glass window, a parallelogram shaped downstairs with a height of 3.3m and a small room upstairs without windows. The show uses these two spaces to set up two quite distinct rhetorics - downstairs contemporary curatorial and upstairs is intended to evoke classicism and museology. I hope that the two distinctive languages draw attention and alert the viewer to their status as constructed spaces.

FB: The new work shown at Alexia Goethe incorporates recognisable elements of existing sculptures by renowned artists. How did you choose these works?

NH: Not wanting to be difficult, I'd rather not say too much. I would say that the sculptural citations are chosen equally for their meaning as for their form (which is something I find quite complicated to deal with). I could say – in 1997 (when I was 17) I read Herbert Read’s Modern Sculpture, and visited the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Ten years later, on my MA in 2007, I read Miwon Quon's One Space after Another. They are a couple of links in the chain, but doesn’t really say why the chain exists. The work comes from an autobiographical place, but is constructed with the viewer as the end (not as myself). What’s crucial to me, is that there is no need to recognise the references only to pick up on the different languages - for example: abstraction of a Hepworth hole, or the naturalism of a Rodin figure.

FB: And how were the associations cooked up? Could you give us a tour of one of them?

NH: (Reluctantly...) I think that “tour” is just an arbitrary story that just limits interpretation. I want the viewer to build their own tours. Calder’s Flamingo is shorthand for public sculpture, Hepworth and Moore stand in for gender inequality, the Frink horse is there because its there outside (by Cafe Nero) (and to pinpoint the here-and-now), Brancusi's Bird in Space is there as short hand for the question: is it greater to exist in reality than in the mind alone (an ontological argument for the proof of the existence of God). Ten years ago, a friend from my Undergraduate was obsessed about the disappointment of artworks... how the reality never matched the idea.... how the screws were never 100% flush on his laptop. The Bird in Space operates in that liminal place between idea and reality - so highly polished it appears not to have an origin, abstract and non-physical (there are no screws in it), but of course ironically this is in fact the result of massive human endeavour - polishing and polishing to rub off the mark of human touch. So then I think of a quote by Richard Wentworth about the nail "The Chieftain of the wiretribe” where he asks us to "Imagine all the thoughts and all the human reverie that has accompanied this immense catalogue of willfulness. Silly of us onlookers to call it mindless work." And this I link to a passage in the introduction to Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night which talks about the cultivation of Orchids and how the leisure class could be defined by working hard at something unnecessary. And lastly, also contained within Bird in Space, is its equal and opposite - Donatello's Mary Magdalene, whose considerable beauty comes from her materiality (haggard and death-like after forty days in the dessert, carved from a humble piece of wood).

FB: Your sculptures only really come alive when the viewer walks around them and changes his/her perspective on the object. How much is that in your mind when making the work?

NH: The pieces are designed to unfold themselves… to reveal their own making (not their process, but where the idea comes from). I want them to interchange between a cooked synthetic and the raw ingredients (which is my recipe of Hegel and Levi Strauss).

FB: Why white?

Because these are citations, and so I'm harking back to the plaster casts at the V&A. A plaster cast as a mechanical copy. Maybe to evoke objectivity. Also the cast rooms (for me) are shorthand for the mixed feeling we have to colonial Britain. I love the V&A but of course its sits a little uneasily that Victoria and Albert amassed things from all over the world in the way that they did. My grandfather was a tea planter in India – I don’t know what to think. That’s why white.

FB: Do you make the work?

NH: Yes and No. Do you make these questions?

FB: In the past it feels like the process was more present in the work or in the way the work was presented. With the new body of work, the process has been polished away, what is your relationship to process?

NH: I'm mainly interested in meaning. So I'm interested in the legibility of process … how the process is interpreted, and what it means to draw attention to process (be it a normal sculptural processes like Serra's list of verbs ... to cut, to fold etc), or a non-sculptural processes (ie. putting a pink castle on a barge down a canal).

But returning to the citational aspects and collection of references, contained within each of these pieces as mentioned earlier, the finish form and its relation to the idea it was meant to embody is never complete. Perhaps we ‘hide’ the hand, but it is not invisible. Its presence here is made apparent by its absence: the pure white form. In this there is a whole narrative of suppression and expression. The process, as I also mentioned previously, is as much in the viewer, in their perspectival movement around a piece, as it is in the raw hours of studio work.

FB: You enjoy talking about the work to people, is that why you make it?

NH: Yes I enjoy conversations about the work – normally they spark off further conversations about something else altogether, and those conversations normally end up in the work. I’m interested in the trajectory of ideas to realization … talking, writing, making – and then in the reverse order… unmaking, reading, listening. I find communication extraordinary – I never know if I’m on the same page. (Do you know what I mean?).

FB: When is a work finished?

NH: When the show comes down.

FB: You made work with a musician, how was that? Is making work with other artists from different disciplines something of interest to you at present?

NH: Frank! You came to the Cello String sculpture 5 years ago! … Yes? Actually I was collaborating with a writer/actor/filmmaker. In short, yes, very much. I love mis-linking things… serialist music and Brecht, Debussy / Impressionism etc. Translation seems to be very pertinent in many ways – so I think that sort of openness to other disciplines as very helpful.

FB: The pieces at Tate and at Southbank involved young people. What did they bring to your practice?

NH: Sometimes Artists bring their practice to participation project. In my case I almost feel I’ve brought my participation project to the commercial gallery… the entire body of work for this solo show has grown from questions that arose working with young people during the projects at Tate and Southbank – both concerning authorship and interpretation. The challenge was to try to bring together multiple voices into a singular object where that process was somewhat visible, but the final object had sense of its own autonomy. I’m still in the middle of unpacking the questions those projects threw up.

FB: What gets you going in the morning?

NH: Coffee.

FB: What is next for you? are you delving further into this current line of enquiry or are you pushing to new territories as well as going abroad for new shows?

NH: Well I had a problem conversation with Kathleen Madden (who was doing a piece for Artform.com). We haggled over the Raven or the Coyote and the leopard – which were the trickster, which was the liminal one. I had got in a muddle. Then we argued about whether the arrangement of the works did more to help unravel or to obfuscate. At the moment she’s won this argument. Which has given me a load more work to do. My solutions to unravel this mess is, I want to make the compounds both tighter, but also their glue weaker. It requires more complex objects - ones that contain compound-perspectives - Thanks Kathleen.

FB: Thank you Nick.

Future projects include a group show at Leighton House in June 2010, a show at Eyebeam, New York in the autumn and a show with Arthur Fleishmann at the Slovak Embassy in London in 2011.

Franck Bordese

Courtesy of Nick Hornby

Courtesy of Nick Hornby

Courtesy of Nick Hornby