Friends of London. Artists from Latin America in London From 196X – 197X, part of Curators’ Series at David Roberts Art Foundation.

What was the inspiration for this exhibition? Where does the title Friends of London come from?

In the late 1960s and all through the 1970s London became the destination for a number of artists coming from Latin America. Most of them are still fairly unknown to audiences here, so through this exhibition we wanted to trace their steps in the capital, look at the works they produced whilst they were here and at the different ways in which they were influenced by and contributed to the local art scene.

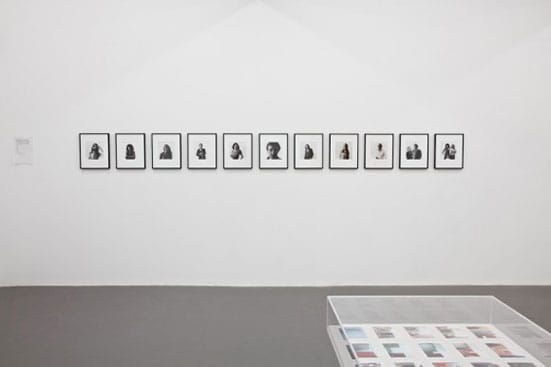

This exhibition takes its title from a work by David Lamelas, London Friends 1974, in which he had his closest friends were photographed by a fashion photographer. For any one who moves to a foreign country, friends become an extended family, and in many ways, this work encapsulates many of the ideas behind the exhibition: how do you build your own sense of belonging in a context that is foreign to you?

However, it is important to note that the artists in this exhibition were not a unified group, in fact, some of them didn’t even know each other. Nonetheless, there were some collaborations amongst them. For example, Leopoldo Maler invited Felipe Ehrenberg to Silence, a show he organised at the Camden Art Centre in 1971. Likewise, Ehrenberg published the works of Ulises Carrión and Cecilia Vicuña through his imprint Beau Geste Press in Devon. Also central to their experience of London was the fact that they were all very well received by artists and curators working in the city and they very quickly established links with a local scene and were thus able to continue their work here.

Could you tell me something about why London became the home for a number of avant-garde artists from Latin America from the late 1960s to the early 1970s?

The reasons why these artists came to London vary according to their personal circumstances, for example, Felipe Ehrenberg arrived in London to avoid the increasingly politically and socially oppressive conditions in his country Mexico, others such as Cecilia Vicuña arrived here with a grant to study and during her stay in London the political situation in her country, Chile, worsened and she couldn’t go back. However, not all of them were escaping politically oppressive regimes, for example, Diego Barboza came to London from Venezuela to study and when his grant expired he returned to Caracas.

How did their experiences in London influence these artists’ work?

London was perceived as a place for experimentation, there was a democracy in place and individual freedom, and at the time there were numerous liberation movements that made the city even more appealing. These artists responded to the city in very different ways, for example, Vicuña’s work became more politicised while she was in London, she was one of the founder members of Artists for Democracy and most of her work during that time is a direct attack on Pinochet’s 1973 coup d’etat. In contrast, for Barboza his time in London was an opportunity to experiment with a more performative approach to art and he embarked on a series of experiences or collective public actions that included the participation of the passers-by. Oiticia experienced a period of transition in London, from his participatory works to a more obscure and sexual work. In contrast, Ehrenberg’s journeys and walks in the city dealt with the experience of being an outsider in exile. For all of them London was a period of great productivity during which they established new relationships between their artistic practices and poetics, conceptualism, collaboration, participation, politics, activism and situationism.

Many of these artists have been neglected by the canon of British art history. Why do you feel it is so important to reassess their critical reputations at this time?

I think it is important to acknowledge that during the 1960s and 70s London was receiving a great deal of artists coming from different parts of the world who were actively contributing to the art scene of the moment. Guy Brett pointed at this particular period in his text Internationalism among artists in the 60s and 70s, published in 1989. It is only fair to acknowledge that since then there have been some efforts to recover certain figures who had fallen outside the canon of British art history, however, the activities of the artists of this exhibition in London have never been properly assessed.

Could you say something about the curatorial process you and Pablo established together? How did you decide what material to include in the exhibition and how to organise it?

We wanted to focus on the most innovative aspects of these artists’ production during their time in London. It was difficult because a lot of the works produced here were actions or events that were never recorded and we wanted to actualise what they did, to give it a second life or to re-activate it. We also wanted to insert it in the present and make it relevant to today’s approaches to art, not to look at it as an isolated event in recent history.

I was interested by the comment in your exhibition guide that you have tried to avoid ‘archive mania or necrophilia’? Could you say more?

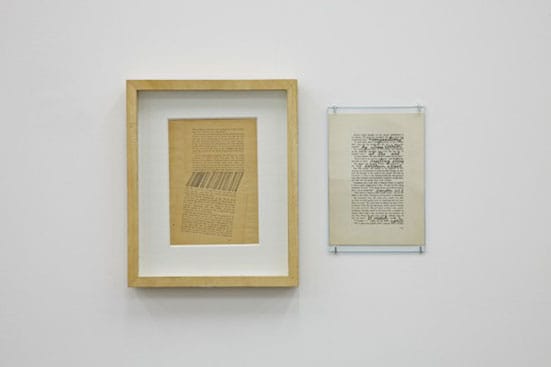

It has become increasingly fashionable to work with archives. The fact is that archive material can give you a very different approach to an artist work or a period, however it can also be very easily fetishised and we wanted to avoid this. We included original archive material with photocopies and didn’t establish a differentiation or a hierarchy between them, this way we tried to make this material more accessible instead of presenting it as some kind of dead document that returns from the past. The main challenge for us was how to reactivate and actualise works and memories through the use of the archive and document, so that they become relevant to the present.

Could you talk about the importance of artists’ networks, as demonstrated in your exhibition, and in the art world today?

I think it is important to look at how artists established their own networks of exchange and how they influenced each other because this is a process that bypasses the institution and the market interests, it is a much more organic process that sets up alternative channels for the circulation of information and artistic initiatives. I think it is important to continue assessing these exchanges, mostly today when the art world has become so institutionalised.

http://davidrobertsartfoundation.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Friends-of-London-Leaflet4.pdf

Ali MacGilp

Installation view. Image: Matthew Booth.

Installation view. David Lamelas, London Friends, 1974. Courtesy of the artist and Sprueth Magers Berlin London. Image: Matthew Booth.

Installation view. Diego Barboza. Courtesy of Colección Diego Barboza. Image: Matthew Booth.

Installation view. Ulises Carrion. Courtesy of Document Art Gallery. Image: Matthew Booth.

Cecilia Vicuna, Ruca Abstracta, 1974/2013. Courtesy of the artist and England & Co. Image: Matthew Booth.

Installation view. Leopoldo Maler, Crane Ballet, 1971. Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria Fine Art, New York. Courtesy: Matthew Booth.